Article

How Can We Protect Our Skin?

Skin is the largest organ of the human body; it covers approximately two square metres in adults and accounts for 8–16 % of total body mass. It is essential to recognise that skin is a dynamic interface between the body and the environment. The integument forms a continuous barrier that limits transepidermal water loss and blocks…

Skin is the largest organ of the human body; it covers approximately two square metres in adults and accounts for 8–16 % of total body mass. It is essential to recognise that skin is a dynamic interface between the body and the environment. The integument forms a continuous barrier that limits transepidermal water loss and blocks entry of chemical and microbial agents. Through its network of eccrine glands and cutaneous vasculature, it regulates core temperature by evaporative cooling and peripheral blood flow.

What is skin composed of?

Skin is organised into three contiguous layers that differ in structure and function. The outermost layer, the epidermis, is a stratified squamous epithelium 0.05 mm thick on the eyelids and up to 1.5 mm thick on the palms and soles. It comprises four to five sub-layers of keratinocytes progressing from the mitotically active stratum basale to the cornified stratum corneum. Lipids secreted in the stratum granulosum form a hydrophobic barrier that limits transepidermal water loss and impedes microbial entry. Renewal of the epidermis occurs every 28–40 days as basal cells migrate and differentiate, then desquamate from the surface.

Beneath the epidermis lies the dermis, a fibro-elastic layer 1–4 mm thick that confers tensile strength and elasticity through interlaced collagen and elastin fibres. It is subdivided into the superficial papillary dermis and the deeper reticular dermis. Eccrine glands release a hypotonic serous secretion that mediates thermoregulation; sebaceous glands produce sebum, an oily substance that maintains skin surface pH and antimicrobial defences.

The deepest layer, the hypodermis, consists primarily of adipocytes interlaced with loose connective tissue. Adipose thickness varies by body site and nutritional status, providing insulation against heat loss, mechanical cushioning, and a reserve of triglycerides that can be mobilised for systemic energy needs.

Collectively, these three layers regulate body temperature via vasodilation or vasoconstriction of dermal vessels and evaporative sweat secretion, synthesise vitamin D from 7-dehydrocholesterol under ultraviolet-B exposure, and provide sensory discrimination through encapsulated and free nerve endings.

Why does skin need protection?

Ultraviolet radiation, pollution, cigarette smoke and repeated mechanical trauma damage epidermal lipids and extracellular matrix proteins. These insults lead to transepidermal water loss, inflammation, collagen fragmentation and accumulation of DNA mutations. Chronic ultraviolet exposure is the dominant environmental driver of cutaneous carcinogenesis. UVA and UVB photons generate cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and 6-4 photoproducts; when these lesions escape nucleotide excision repair they trigger mutations in TP53, CDKN2A and other tumour-suppressor genes, increasing the risk of basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma and melanoma. Tobacco smoke delivers polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and reactive oxygen species that up-regulate matrix metalloproteinases, reduce collagen synthesis and promote telomere shortening; epidemiological studies show a 1.5- to 2-fold higher incidence of squamous cell carcinoma in smokers compared with non-smokers. As a result, the skin may develop dryness, redness, hyperpigmentation, wrinkles or neoplasia. Protection reduces these adverse outcomes and preserves barrier function.

How can daily habits protect the skin?

Sun protection is the most studied intervention. A broad-spectrum sunscreen with SPF 30 or higher, applied as a thin film over exposed areas and reapplied every two hours, decreases ultraviolet-induced erythema and photo-ageing. Seeking shade and wearing protective clothing further reduce exposure. Gentle cleansing with lukewarm water and mild cleansers removes pollutants without stripping the barrier. Moisturisers containing ceramides or petrolatum restore lipids and prevent transepidermal water loss. Smoking cessation and adequate hydration support wound healing and collagen integrity.

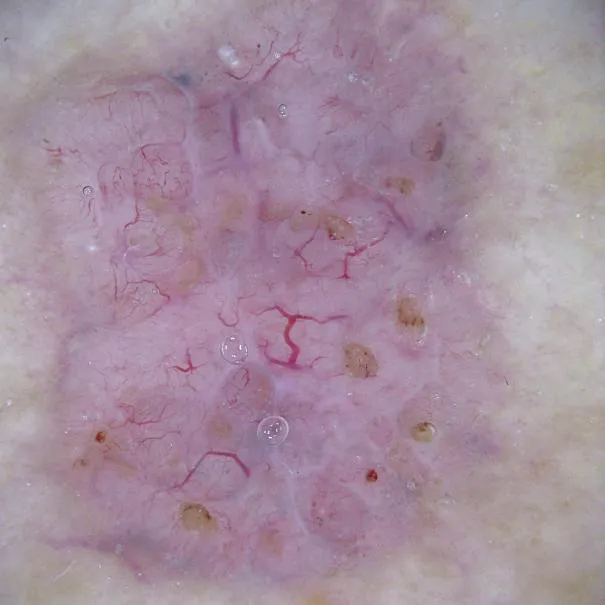

Does dermoscopy improve early detection?

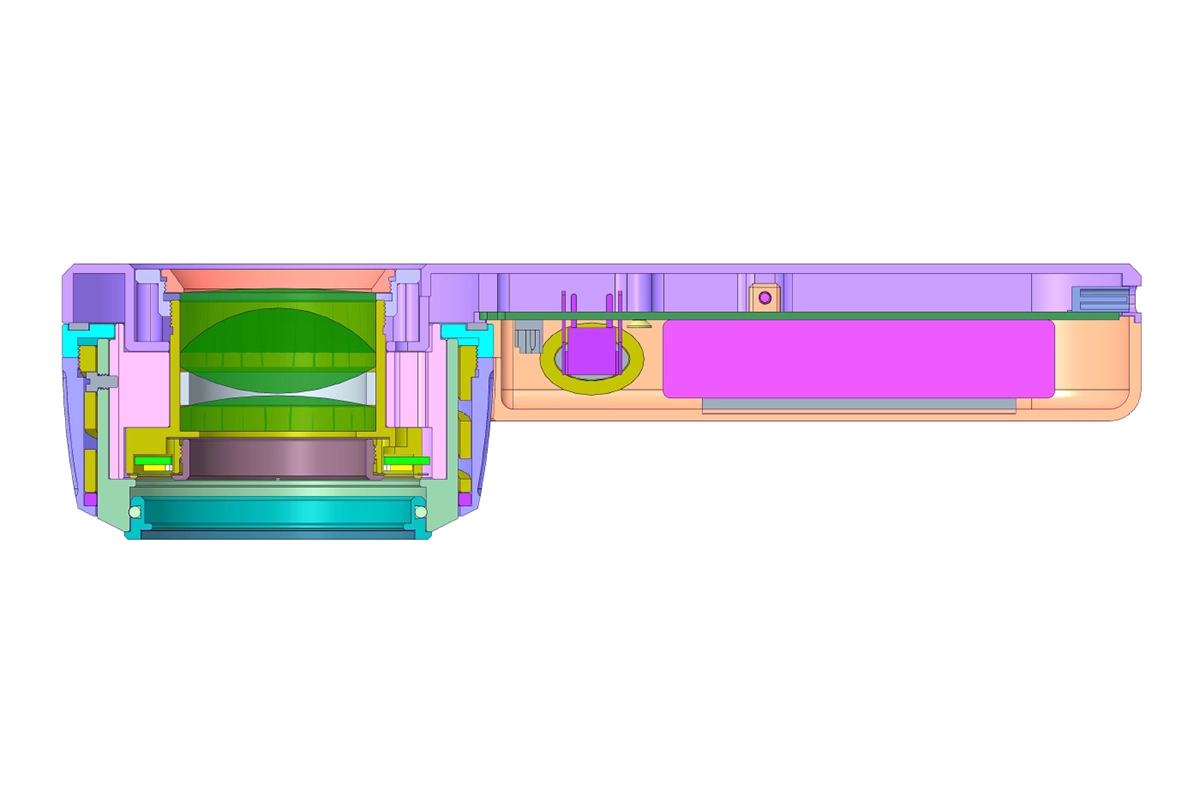

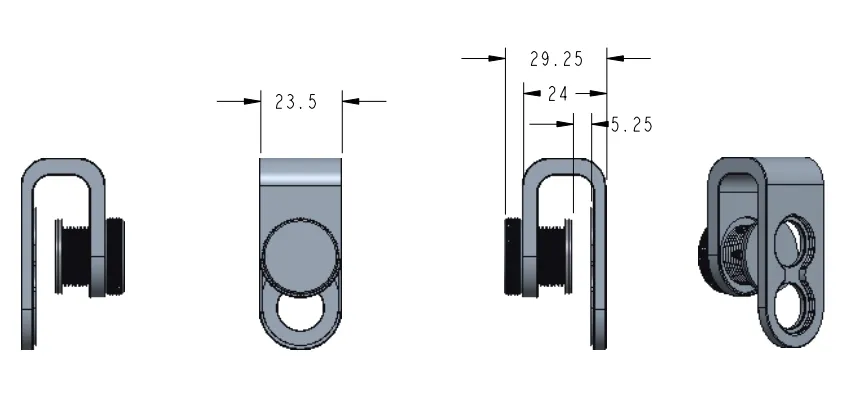

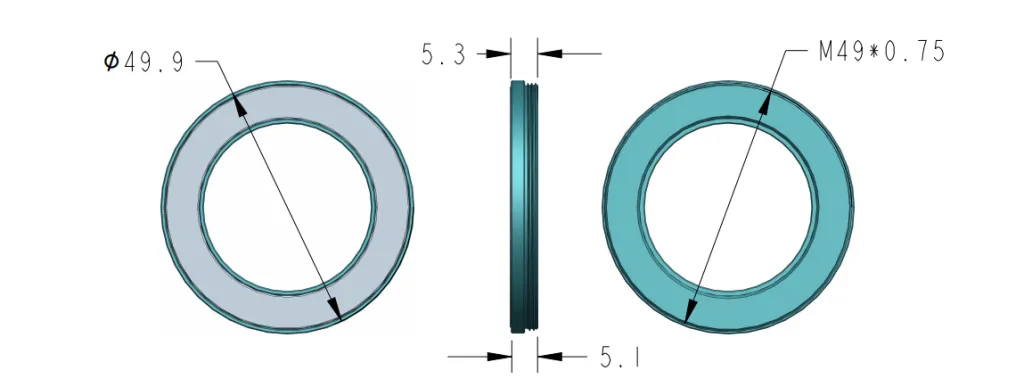

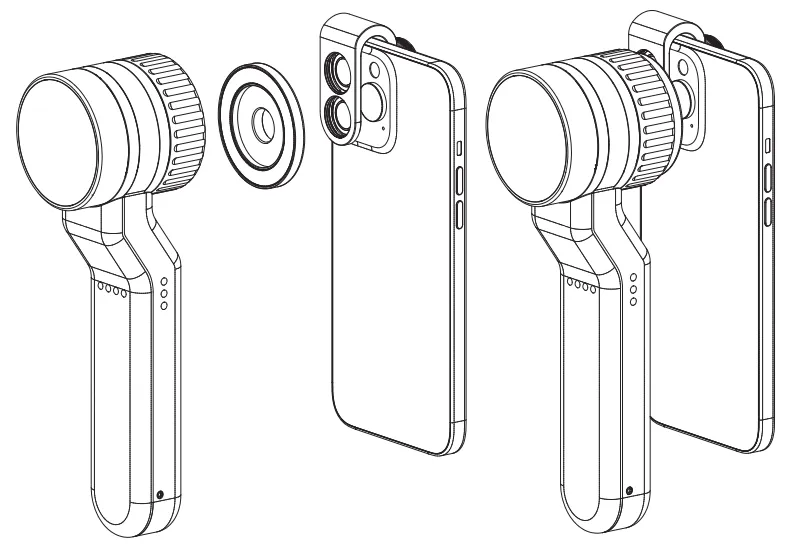

The IBOOLO dermatoscope provides 10X polarised magnification and can reveal subclinical pigment changes, vascular patterns or scale alterations before they are visible to the naked eye. The IBOOLO DE-4100 PRO is currently the most comprehensive dermatoscope offered by IBOOLO, providing excellent support for the early screening of skin cancer. The DE-4100 Pro features four lighting modes: polarized, non-polarized, amber-polarized, and UV light. Polarized light allows observation of the dermis layer of the skin, while amber-polarized light is designed to accommodate different skin tones and better visualize the edges of skin lesions. Non-polarized light is used to examine the epidermis layer, and UV light is employed to detect pigmentary disorders and fungal infections.

What skin abnormalities should prompt you to seek medical attention?

Seek care for any lesion that changes in size, colour, or texture, or that presents with bleeding, oozing, or persistent ulceration. These include rapidly expanding erythematous plaques that may signal cellulitis, purpuric or necrotic areas suggesting vasculitis, and widespread blistering or erosion that can be early manifestations of immunobullous disease. In addition, sudden eruption of a painful, vesicular rash with fever may indicate herpes zoster, while a non-healing ulcer or a pearly nodule that bleeds easily can be a basal cell carcinoma. Any oozing lesion accompanied by systemic upset must be evaluated to exclude necrotising fasciitis or drug hypersensitivity syndrome.